For the love of logic, put the touch back in touchdown

We come seeking understanding

of the Ubiquitous Orange Obelisk

By TD Wood

Editor, Fixtherule.com

One of the lesser-known attributes of pylons is their unintentional comedic value:

CBS Sports (Thanksgiving 2021)

Beyond causing surprise face-plants, what is the purpose of a pylon?

According to Sports Illustrated, pylons (in the form of red flags) first appeared at the 1962 Hall of Fame Game. Foam-type pylons debuted in January 1973 during Super Bowl VII and have been part of the game since. Cameras were added to them in 2012, inserting “pylon cam” into football’s lexicon.

But what are pylons — 18 inches high, 4 inches by 4 inches square from top to bottom — intended to do? The SI article mentions they play a “boundary-defining” role in the game. OK. What boundaries do they define?

In search of an answer, we turn to the 2024 NFL Rulebook.

The Rulebook contains approximately 62,450 words. Pylons, for all their impact in so many games, are mentioned just 12 times. We will quote all 12 references.

In Rule 1 (The Field), Section 2 (Markings), Article 2 (Inbound Lines), we learn they mark junction points of the goal line (which is inbounds) and sideline (out of bounds):

The four intersections of goal lines and sidelines must be marked, at inside corners, by weighted pylons. In addition, two such pylons shall be placed on each end line (four in all).

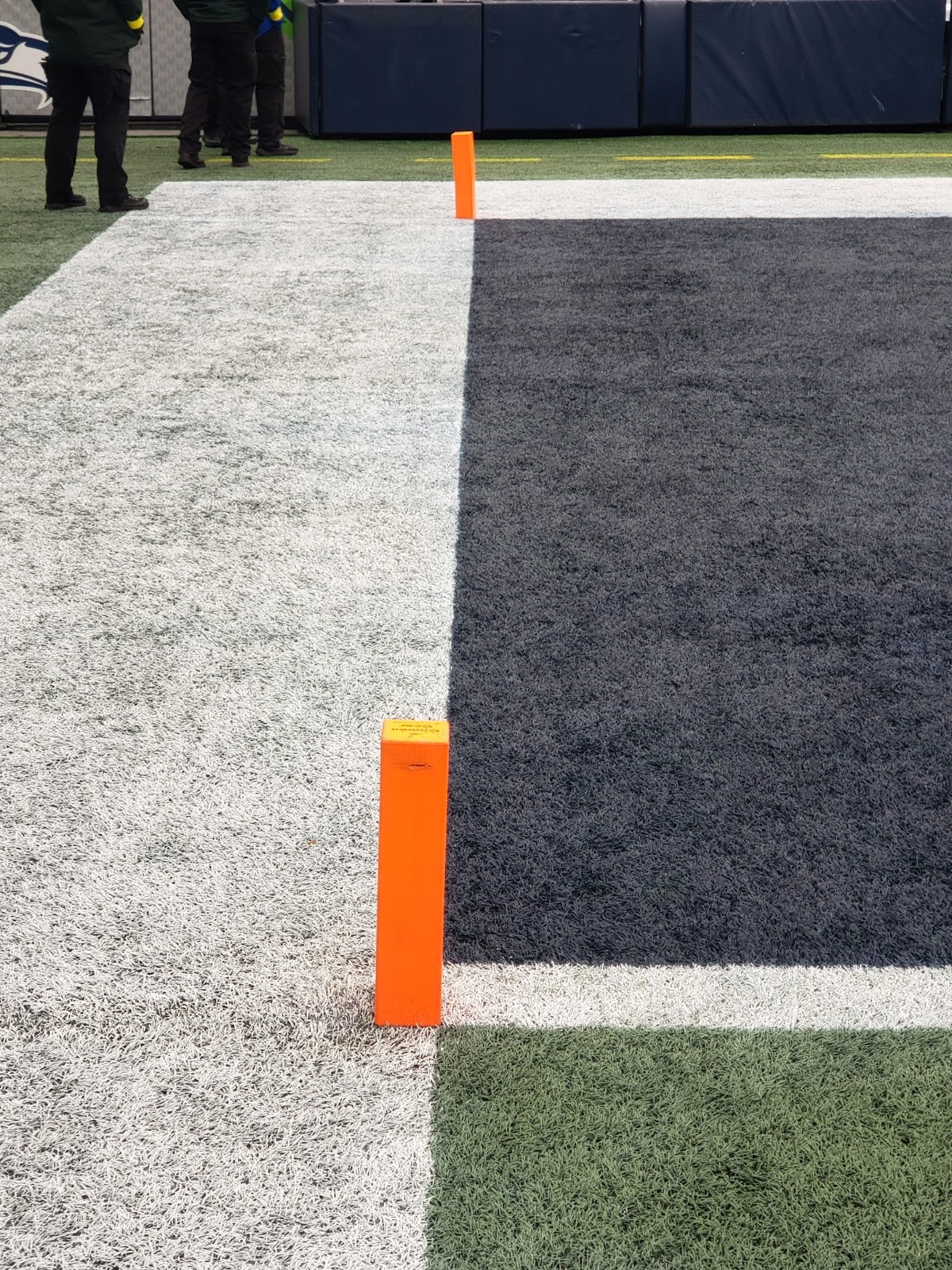

FixtheRule.com

The first sentence in that explanation is essentially a repeat of what is presented in the Rulebook’s first mention of pylons, found in Field Markings, point 5:

The four intersections of goal lines and sidelines must be marked at inside corners of the end zone and the goal line by pylons. Pylons must be placed at inside edges of white lines and should not touch the surface of the actual playing field itself.

Hold on. Check out that second sentence. If we are reading it correctly — that pylons “should not touch the surface of the actual playing field itself” — that indicates pylons are positioned out of bounds. That’s evident in our photo above and these two in-game images:

Fox Sports

NBC Sports

What are the parameters of the “playing field”? We’re straying close to legalese here, but in Rule 1 (The Field), Section 1 (Dimensions), Article 2 (Field), the Rulebook states “The Field includes the Field of Play and the End Zones. The Field will be rimmed by a solid white border a minimum of 6 feet wide along the end lines and sidelines.”

So are the end zones separate from the 100 yards of space that separate them? Look at the Rulebook’s Field Markings section, this time in point 1, where it again tells readers “The playing field will be rimmed by a solid white border six feet wide along the end lines and sidelines.” The diagram that appears below the headline “Plan of Playing Field” (the section before Field Markings), shows that six-foot boundary frames both end zones as well as the 100 yards between them.

In our quest for a common-sense interpretation, to us that indicates that the end zones are part of the “playing field.” We believe most fans would agree with that common-sense point of view.

If pylons are positioned out of bounds (not touching the surface of the actual playing field), we have a potential conflict with this Rulebook entry, found under Rule 11 (Scoring), Section 2 (Touchdowns), Article 1 (Touchdown Plays), points (b) and (c):

A touchdown is scored when:

(b) a ball in possession of an airborne runner is on, above, or behind the plane of the goal line, and some part of the ball passed over or inside the pylon

(c) a ball in player possession touches the pylon, provided that, after contact by an opponent, no part of the player’s body, except his hands or feet, struck the ground before the ball touched the pylon

So here we are told a ball possessed by a player can pass over a pylon or make contact with a pylon and result in a touchdown. This, we speculate, is the source of the odd-sounding “goal line extended” exception occasionally mentioned by TV analysts and rule interpreters when justifying pylon pokes and wave-overs as touchdowns.

Ball carriers too often (for our tastes) take advantage of this extended goal line. When they draw near a pylon, typically because a defender has closed off their path to the end zone, the goal line — as if touched by Tinkerbell’s wand — is suddenly extended by the pylon’s 4″ x 4″ footprint. To us, that seems both odd and unfair to the defense.

The pylon, by Rulebook explanation and by the eye test, is out of bounds. If a ball carrier’s foot stepped on that six-foot white sideline an inch or two in front of where the pylon is located, he would be ruled out of bounds. But if he touches the pylon, he’s good. That seems bizarre — that this 4” x 4” space on the sideline magically qualifies as touchdown territory. We’ll let Vizzini from The Princess Bride make the call: “Inconceivable!”

The Rulebook reinforces that assertion clearly, if illogically (to our way of thinking), under Rule 3 (Definitions), Section 11 (The Field), Article 3 (End Zone):

The end zone is the rectangle formed by the goal line, the end line, and the sidelines. The goal line and the pylons are in the end zone.

This is part of the “goal line extended” rationale, and we respectfully disagree with it. How can pylons be simultaneously in the end zone (inbounds) and on the sideline (out of bounds)?

First, we believe the goal line should remain a constant, a fixed width, never “extended” just because a ball carrier is lumbering in its vicinity.

Next, pylons are located on the sideline. And sidelines are out-of-bounds territory. So says Article 8 (Sidelines) of Rule 3 (Definitions) and Section 11 (the Field):

The sidelines are the lines on each side of the field and are perpendicular to the End Lines (defined as “10 yards from the goal line and at the back of the end zone,” in Article 2 of Section 12). The Sidelines separate the Field of Play from the area that is out of bounds.

Clear enough. So let’s simplify this: Field of play = inbounds. Sidelines = out of bounds.

Accordingly, we believe any ball that passes over or hits a pylon — which is positioned on the sidelines, which is out-of-bounds territory — should be considered out of bounds. Is that not a sensible conclusion?

Instead, goal lines have 4” by 4” areas (where pylons stand) on each end that extend the legalized scoring area into out-of-bounds territory. This creates an extra-wide goal line, 4 inches on each end, that has become a mighty handy add-on for ball carriers over the years. We are mystified by this puzzling rationale.

Our hunch is this ruling, this breach of logic, exists because football’s caretakers years ago became overzealous in their desire to encourage scoring, especially scoring plays that look exciting.

Pylon dives are routinely the subject of highlight reels, promotional clips and commercial-break teasers. Fans involuntarily feel their teeth clench and fists tighten when watching a runner dash down the sideline with defenders in hot pursuit. Will he get to the pylon?!

Stretching for a pylon is similar to a sprinter leaning for the tape to be the first to break the finish line, just with a much higher sense of danger. High drama. Maximum effort. Thrills and chills.

YouTube is well-stocked with compilation videos focused on pylon reaches. Even NFL Films created a feature devoted to pylon-diving, during which tight end Darren Waller says, “Oh yeah; diving for the pylon is definitely sexy.” Retired running back Ricky Williams adds “It looks good, putting that ball on the pylon.”

We get the excitement factor. We just don’t understand how hitting an object that is positioned out of bounds translates into a touchdown. To us, since a pylon sits out of bounds, it should instead be used to indicate when a player has strayed out of bounds. That’s the boundary a pylon should be used to define. Instead, we should wonder: Will he get to the end zone?

Yet here’s another Rulebook pylon puzzler, also part of Rule 3 (Definitions), this one in Section 20 (Out of Bounds, Inbounds, and Inbounds Spot), Article 1 (Player or Official Out of Bounds):

A player or an official is out of bounds when he touches a boundary line, or when he touches anything that is on or outside a boundary line, except a player, an official, or a pylon.

Why does hitting a pylon get a pass here? We’re not sure. We see the pylon exception again in Section 20, Article 2 (Player Inbounds):

A player who has been out of bounds re-establishes himself as an inbounds player when both feet, or any part of his body other than his hands, touch the ground within the boundary lines, provided that no part of his body is touching a boundary line or anything other than a player, an official, or a pylon on or outside a boundary line.

Reading rulebook legalese is not scintillating stuff, we realize. We simply quote these rulings to point out what we perceive to be unintended contradictions.

What about loose balls, such as a fumble or a rolling punt? We read the following in Rule 3, Section 20, Article 3 (Ball Out of Bounds), Item 1 (Ball in Player Possession) and Item 2 (Loose Ball):

Item 1. Ball in Player Possession. A ball that is in player possession is out of bounds when the runner is out of bounds, or when the ball touches a boundary line or anything that is on or outside such line, except another player or official.

No mention of a pylon there. Next:

Item 2. Loose Ball. A loose ball that is not in player control is out of bounds when it touches a boundary line or anything that is on or outside such line, including a player, an official, or a pylon.

So a tumbling punt that hits a pylon is out of bounds. But a ball carried by a player that hits a pylon is considered a touchdown? That’s just wild.

For the record, this situation also gets a mention in Rule 15 (Instant Replay), Section 3 (Reviewable Rulings), Article 5 (Plays Governed by the Boundary Lines), Item 5 (Loose Ball):

Item 5. Loose Ball. Whether a loose ball touched a boundary line, anything on the boundary line, a pylon, or an object.

Same deal; a loose ball is ruled out of bounds when it contacts a pylon. And that makes sense since a pylon, after all, is out of bounds.

So there you have them, all 12 Rulebook references to pylons.

Pylon dives have become such a commonplace element in today’s game that we would hope rulemakers might reconsider the scoring leniency that the current rule allows.

This website advocates that ball carriers be required to make physical contact with some portion of the end zone in order to be awarded a heaping helping of six points, football’s most lucrative payout. Instead, fans witness increasingly frequent pylon wave-overs as ball carriers, seeking to avoid tacklers, run wide of the end zone without touching it, merely catching a wisp of its airspace with the ball while their feet land far out of bounds. These are touchdowns by technicality. Six points by sleight of hand.

Airspace touchdowns and no-touch two-point conversions are unsatisfying to watch and unworthy, we believe, of the points they put on the board. ATDs leave fans feeling unfulfilled, shortchanged, gypped.

To us, ball carriers should focus on the end zone instead of pylons. They should keep inside a pylon’s inside edge and make contact with the designated scoring area. Right now, pylons have become antennas of absurdity, totems of technical touchdowns that warp the integrity of the boundaries that the sidelines are supposed to represent.

Of all the pylon pokes we have witnessed, none made us howl in disbelief more than this rule-stretching lunge by Kansas City’s Patrick Mahomes. Fans love his daredevil unconventionality, but on this dive he barely grazes the outside of the pylon, meaning the ball (with a diameter of 6.7 inches) is occupying about a foot in out-of-bounds airspace. Yet he still gets six points — all while never touching the end zone:

Fox Sports

We think the game would be well served if it reconsidered how it adjudicates pylon dives. Thanks for reading and considering our point of view.

Write: editor@fixtherule.com